YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE

After the great success of Shuffle Along, tensions developed between the creative team of Sissle and Blake and Miller and Lyles. Sissle had served more or less as the foursome’s voice with the show’s white producers; the comedians suspected that he was taking advantage of the situation, and taking a bigger cut than he deserved. Meanwhile, Sissle and Blake as songwriters were earning additional income from music publishing and recordings that Miller and Lyles did not share. The comedians decided to abruptly quit the touring production of Shuffle Along in late May 1923 to launch their own version.

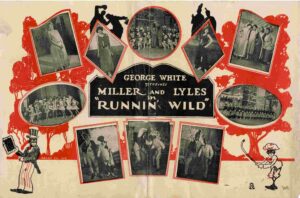

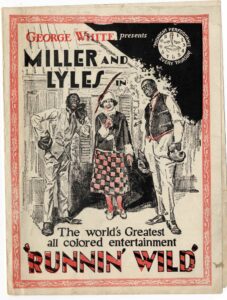

In mid-July 1923, George White (of White’s Scandals fame) announced a new edition of Shuffle Along would open in the fall, featuring Miller and Lyles, with music by James P. Johnson and lyrics by Cecil Mack. The lead duo were to be paid $2000 a week. This was a clear slap in the face to their producing partners, who were planning to continue touring the original Shuffle Along that fall. After some legal wrangling, Miller and Lyles dropped the Shuffle Along name, and their show would eventually open as Runnin’ Wild.

Miller and Lyles’s Runnin’ Wild opened in late October 1923, and racked up an impressive 228 performances when it closed in May of 1924. The show sported a huge cast—advertised as a 100 strong—and producer George White promoted the accompanying band as “Rick’s Shuffle Along Orchestra”—a clear slap in the face to Sissle and Blake. (Later on, the band was renamed the “Runnin’ Wild Orchestra” after the show was established.)

Even as Runnin’ Wild was reasonably successful, the white audience’s appetite for “negro” productions was beginning to lag. Many white reviewers expressed at best lukewarm enthusiasm for Runnin’ Wild on its opening, complaining that the earlier shows had set the standard so high that the only option for new productions was to be even faster and funnier—which could overwhelm the audience. The critic in the Brooklyn Eagle wrote: “To arouse new attention, the negro show will be obliged to exhibit even more hysteria, better dancing, and worse singing and comedy than it now possessed.”

The critic warmed to only two moments in the show: The singing of “Old Fashioned Love” and the finale, in which “six or seven of the loveliest of the chorus participate. It is a frame, even as the whites have shown, of brownish girls, which the whites would never have shown, reclining in posture which, for want of a better term, might be called artistic. They are nearly, if it is necessary to say it…nude. It is very, very beautiful.”

This reviewer made no mention of what would become the show’s most famous dance number, “The Charleston.” The dance was performed as part of a medley of fancy steps by the chorus girls and lead dancer Tommy Woods at the close of the first act. It became a rage in ballrooms, abetted by the quick release that November by Victor of “The Charleston Medley,” described as a “fetching and timely fox trot.”

Of course, Sissle wasn’t about to let his old competitors take full credit for popularizing “The Charleston.” To his hometown paper, he commented: “The ‘Charleston’ isn’t as new as some folks might think. They were dancing the ‘Charleston’ fifty years ago at Savannah, Ga. … because that’s when I learned it.” Once the Charleston became a fad among white dancers, many others took credit for originating the dance. It of course incorporated movements that were common in other African American dance forms, so it’s not surprising that it had many claimants to be its creator.