YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!

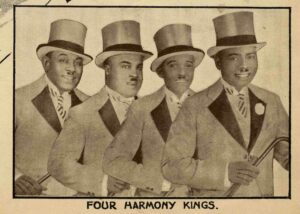

In the summer of 1921, a close-harmony group, the Four Harmony Kings, were added to the production of Shuffle Along. The Kings had been touring vaudeville successfully since the mid-teens, billing themselves as “A Symphony of Color.” The group not only sang but played instruments and even did some comic routines. The group’s leader, Ivan Harold Browning, would soon replace Roger Williams as the show’s lead while still singing with the quartet. In a special spot during the second act, the group sang favorites like Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe,” “Ain’t It a Shame,” and “Snowball.” But they also undertook sophisticated vocal works including William Horace Berry’s poem “Invictus” as arranged for orchestra by Bruno Hahn.

We can get a sense of the Kings’ vocal style through a record they made while appearing in Shuffle Along: “Goodnight, Angeline,” which was one of Sissle and Blake’s first hits (co-written with James Reese Europe). Recorded for the black-owned label, Black Swan, the disc opens with a brief piano introduction that may have been played by Blake—it’s impossible to know, although it is similar in style to Blake’s accompaniments for Noble Sissle from the era. The Kings then perform the song a cappella, in a complex arrangement that reflects standard vocal-harmony style of the era. Indeed, if you didn’t know their race, you probably couldn’t identify this performance as being by an African-American group. Not surprisingly, the attraction of acts like the Kings was their “sophistication”; white audiences marveled at the ability of African American vocalists to perform in a “refined” style.

Blake was elated by the impact of the quartet, again emphasizing their education and the class they brought to the show: “They were sensations. All college men, not only could they sing, but they were very polished and stylish. They came out on the stage dressed in gray evening clothes. The suits were cutaway, and their top hats, ties, and shoes were also matching gray. They had everything. After their performance, Flo Mills had to be behind to top them. No one else could follow—that’s how great they were.”

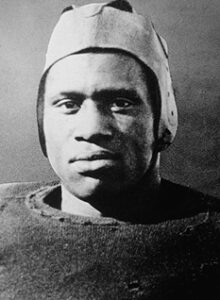

At one point, Hann took a brief leave-of-absence from the show. The search was on for a replacement who could, if not exactly equal Hann, at least be close to his talents. Browning described how he found the perfect substitute. He and his wife were out walking with another young couple. His friend was a recent graduate of Rutgers University, an athlete named Paul Robeson:

When I mentioned to Paul that our bass singer was leaving the show for a short time and that we had to find a bass to replace him, Paul looked at me and said, “You’re looking at a bass singer!” Paul was quite emphatic about it, and when I told him to stop kidding, he said, “I am not kidding; I am your bass.” So I told him to come to the show and see Eubie and me… After Paul sang about seven or eight bars, Eubie jumped up and exclaimed, “That’s the man!”

However, Blake and his partners were concerned about Robeson’s ability to act. The young singer had never been on the stage before. “Both Browning and I agreed about Paul’s voice,” Blake explained. “He was able to learn the songs and small speaking parts in a matter of hours, but moving his massive body around the stage was a challenge. Paul stood out like a sore thumb.” In fact, Sissle commented, “That guy’s too big!” Sissle was proven right on Robeson’s opening performance. Blake took Robeson to behind the curtain and the two men looked through the peephole at the audience filing into the theatre:

We looked at the audience filling up and I pointed to the spotlight in the back of the hall. I cautioned Paul that when he came out onto the stage, above all, he was not to look at the spotlight, because it would blind him. But, sure enough, when they came out onto the stage, Paul looked straight into the spotlight and was blinded. … He fell right into the footlights, which sloped down into the stage gutter, and pop, pop, pop went the broken lights. … But you know, it never fazed him; he got right up and went into the songs. It takes guts to do what that guy did. I’ve known people who had been on the stage for years and they couldn’t have pulled that off.

Robeson won audiences over and stood out from his partners in the quartet as well as the other cast members. Blake explained:

The white audiences—they were all white then—liked him. Paul sang some of Hann’s solos, including “Invictus,” “Mammy” (we sang a lot of mammy songs in those days), Will Marion Cook’s classic “Rain,” and a favorite of Paul’s, “Old Black Joe.” “Old Black Joe” was our last number and Paul just loved it. Paul was still huge on the stage; he was so big that we had him sit down while we sat around him on the stage. But you could see that Paul, awkwardness and all, was going to be a hit, even then.

Early in 1922, Robeson left the company to join the cast of Mary Hoyt Wilborg’s play, Taboo, and Hann resumed his role with the quartet.

The Kings would continue their associate with Sissle and Blake in their next show, In Bamville, which became Chocolate Dandies. They again drew positive attention from the critics, although not always in the way they might have expected: “The Four Harmony Kings…made an enormous hit and all of these smiling, happy relievers of the world’s care took their honors easily, with no airs, no excitement, no affectation. Just blessed “darkies,” like they always are when they amuse and appeal and win us over beguilingly because they are entirely different from less human “white folks,” and always belong to the best of us.” In trying to be complimentary, the reviewer reveals himself to be more than a little racist, or at least supports unfortunate stereotypes about this highly trained musical quartet. Many white critics praised the show’s “eager to please” singers and dancers, another code phrase for “well-behaved Negroes” who wouldn’t challenge white audiences.