YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!

Comedian Johnny Hudgins was hired by the producers of Sissle and Blake’s Shuffle Along followup, In Bamville when it became apparent that the production needed additional comedic talent. Hudgins was a talented mime and eccentric dancer who had established himself by touring with several editions of the Town Scandals revue that was a popular feature on vaudeville. Apparently, it was a good idea to add him to the show, because when it finally opened under the new title of Chocolate Dandies on Broadway, the reviewers reserved their praise for Hudgins’s act. Hudgins developed a unique mimed routine in which he imitated the sound of a solo jazz trumpet, silently mouthing along as cornetist Joe Smith played bluesy riffs off stage. This “Mwa Mwa” routine was a regular show stopper for the production. Smith’s hot playing was also widely admired and regularly drew the attention of audiences and critics.

Variety’s critic reported: “Johnny really scored the individual hit…with his peculiar sliding and eccentric stepping and pantomimic warbling.” The New York Times critic also singled out Hudgins for his “pantomimic performance which was as funny as anything one could hope to witness. He was the regular old negro type in tattered attire, and his dancing was original and pleasing.” The fact that Hudgins’ stage dress corresponded with the “regular old” stereotype undoubtedly aided in his positive reception by the white critics. Besides his dancing,

It wasn’t long before Hudgins’s success attracted the attention of rival producers Lee and J. J. Shubert, who offered the comic dancer double his salary to perform at their Winter Garden theater for Sunday vaudeville shows; The Shuberts coupled this arrangement with weeknight performances in a revue at the Club Alabam, produced by the club’s manager Arthur Lyons. By mid-September, Hudgins had left the Dandies company for these more lucrative offers. Producer B. C. Whitney brought an injunction against the Shuberts and Lyons claiming that he had purchased Hudgins’ services from his previous employer, the producers of the show Town Scandals, for the sum of $251; moreover, he increased Hudgins’ salary from what he received in the Scandals from $125 to $150 a week during the show’s pre-Broadway tour, and again to $200 when Chocolate Dandies opened on Broadway. In his complaint, Whitney explained why he had brought Hudgins into the production: “It became apparent that it lacked a very essential quality in a colored production—the quality of humor and comedy, and I set out to remedy this want and to procure a colored artiste who would be of Broadway caliber…This was a very difficult thing to do. There are not many colored actors who have sufficient ability to create comedy sufficiently original, spontaneous and pleasing [sic] to a New York audience.”

In essence, Whitney was arguing that Hudgins was a unique talent who provided an act that could not be replaced by anyone else. Variety commented on this unheard of development, as no “Negro performer” had ever been judged “unique and extraordinary” before. Whitney’s lawyer went further, enumerating the many ways that Hudgins’ performance was original to himself: “The defendant Hudgins is an actor, dancer, mimic and pantomime comedian of novel, special, unique and extraordinary ability; that he has an original and unique manner of performing a shuffle dance; that he performs negro dances with rare grace and ease; that he goes through the pantomime of singing a song in a most comical manner…and the services rendered by said Hudgins are such that no other performer could be obtained who could perform in like manner.”

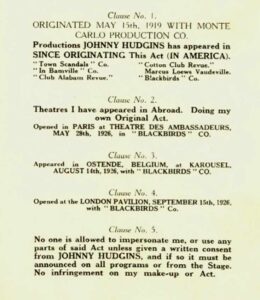

In order to battle this lawsuit, Hudgins was put into the ironic position of having to argue that he was in fact not “unique” in his performance and could be replaced by another actor. Meanwhile, the black press was celebrating the fact that the lawsuit could set a precedent establishing that a colored performer could be considered uniquely talented. Hudgins’ lawyers argued that he had never appeared on Broadway prior to his engagement with Chocolate Dandies and in no way had established a reputation among white audiences. Hudgins’s name did not appear separately in the show’s advertisements or in its on-sight billing, nor was special mention made of him in the show’s publicity. Further, Hudgins himself testified that “I am a dancer like hundreds of others among my people, and there is nothing unique or extraordinary in my steps.” It must have been humiliating for the dancer who indeed had established a unique and applauded routine to have to make this counterargument, but he obviously had no desire to take a pay cut and return to working for Whitney. In fact, during the summer months when Whitney reduced all of the cast’s members by 25% before the show reached Broadway, Hudgins had refused to sign an amendment to his original contract accepting this pay cut. His lawyers argued that Whitney’s ruse in effect voided the original agreement, and that Hudgins had the right to sign with another party at any time. The upshot was that Whitney lost his case, and Chocolate Dandies never recovered from the loss of its biggest box office draw. Ironically, when Hudgins was performing in London in the later ‘20s he actually published a book describing his routines, copyrighting them as his unique creations.