YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!!!

In the annals of theater history, there are many colorful characters among the actors, agents, producers, and critics who populate the Broadway scene. Lew Leslie was undoubtedly one of the most eccentric, with a meteoritic rise and fall worthy itself of a Broadway show. Leslie began his career as a vaudevillian in partnership with Belle Baker, who would become his first wife, but quickly switched to being an agent/producer. His big break came when he was hired to produce a revue at Broadway’s Plantation Club in 1922, and was able to lure away Florence Mills from the cast of Shuffle Along to be his star. Suddenly finding a mission in life, Leslie became a champion of African American performers.

In 1926, Leslie took Mills to England, along with several other performers including comic-dancer Johnny Hudgens (late of the ill-fated Chocolate Dandies). Titled from Dover to Dixie, the show’s highlight was Mills’ performance of the song “I’m A Little Blackbird,” which she sang after emerging from a giant pie. Capitalizing on the song’s success, Leslie next placed Mills in a revue titled Blackbirds of 1926, which played in Harlem and then Paris. However, just as she was achieving great success, Mills tragically died in 1927, so Leslie had to find a new star for his next production, Blackbirds of 1928. He hired Adelaide Hall to fill the part, along with dancers Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and “Peg Leg” Bates. Leslie hired the white songwriting team of Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh to compose the songs, and several became major hits, including “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” The show broke records for an all-black revue on Broadway, with over 500 performances. However, Leslie worked his cast mercilessly, adding midnight shows to capitalize on the production’s success. He also paid poorly and irregularly—not unusual for the time—so that eventually Hall left the production in disgust after it went out on the road.

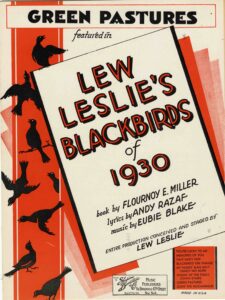

Perhaps under pressure to live up to his image as a champion of black artists, Leslie decided to produce Blackbirds of 1930 using all black-talent, even behind the scenes. He turned to Flournoy Miller, who had recently split with his stage partner Aubrey Lyles. Lyles had decided to move to Africa to escape American racism, leaving Miller high and dry. In Lyles’ place, Miller partnered with Mantan Moreland, who would remain his sidekick for several decades. Miller was hired to write the show’s book, which like most revues was fairly loosely constructed to accommodate the various acts. Ethel Waters—who had achieved great success in Harlem’s nightclubs—was to be the leading lady for the production. Also included were the vocalist Minto Cato, the dance duos the Berry Brothers and Buck and Bubbles, and Blakes’s partner Broadway Jones.

Leslie came to Eubie with a rich offer to compose the score: a $3000 advance (about $45,000 in today’s dollars) to write 28 songs from which several would be selected for the show. Blake was also hired to conduct the orchestra at a promised salary of $250 a week ($3750 in current dollars). This was very good money for the period, considering the Great Depression was just beginning.

For the lyricist, Leslie turned to Andy Razaf, who had scored several hits in partnership with the pianist/singer Fats Waller, among others. Razaf was among the most sophisticated lyricists of the period, bringing a unique combination of wit and a bit of a political edge to his work. When writing for Waller, Razaf said, “you can almost hear how he’s going to sing your words while you’re still writing them down on paper.” His job was to fashion lyrics that fit Waller’s larger-than-life stage personality. But writing with Eubie would prove to be different: “When you’re writing to his music, you never know who’s going to sing it…When I write for Eubie, I think of big sets, a chorus line, elaborate costumes. Of course, Eubie’s melodies lend themselves so perfectly to sophisticated lyrics, and they’re sort of a challenge, too, because musically he’s so far ahead of most contemporary popular composers.” Blake and Razaf hit it off immediately, with the lyricist’s sense of humor strongly appealing to Eubie. The two spent the winter working together, holing up at Andy’s mother’s house in Asbury Park, NJ.

Blackbirds of 1930 was a hugely ambitious production. Typical of Leslie, he couldn’t stop tinkering with its various components, adding new segments and dropping others, while also fussing over every detail—even leaping into the orchestra pit during rehearsals to show Eubie how to properly conduct. Eubie found Leslie difficult to work with throughout the rehearsal process and began to suspect that Leslie was slightly unbalanced. “Somethin’ went wrong with Leslie, somethin’ went wrong with his head,” Eubie told Razaf’s biographer Barry Singer. Dancer John Bubbles noted that throughout the production there was a lot of friction between Leslie and Blake: “Eubie wanted things to go the way he wanted to go, and Leslie wanted things the way he wanted to go.” Bubbles concluded however that ultimately it was Leslie’s show and he could make any changes that he wanted whenever he wanted to do so.

The show’s big hit was the song “Memories of You,” which was introduced in this opening scene by Minto Cato, who was known for her amazingly high vocal range. In the words of the Chicago Defender, for Cato a “high C is low,” and the song was custom tailored to show off her vocal chops. Oddly, Waters, not Cato, made the first recording of the song in August 1930. She says in her autobiography that she was imitating the popular warbling style of Rudy Vallee in her performance, and indeed her exaggerated enunciation and totally unsyncopated reading of the lyrics is much in the style of this popular crooner. Eubie would later regret crafting the song specifically for Cato, saying the song’s wide range limited it to a select group of performers. Nonetheless, it became a hit for Waters and Louis Armstrong, who covered it with his big band, and in the mid-‘50s, it was revived as an instrumental by Benny Goodman, hitting the charts again.