YOUR DAILY DOSE OF EUBIE!!!

James Reese Europe was a key figure in the development of African-American popular music on the New York scene. He was born in Mobile, Alabama, on Feb. 22, 1880, to a middle-class black family. The family moved to Washington when Europe was 10, and as a young teen he established himself as an up-and-coming classical violinist. His teacher was Joseph Douglass, the son of noted African-American author Frederick Douglass and himself a well-known performer in the black community. Coming to New York to pursue his career in 1899, Europe found the classical music world closed to him due to his color. Instead, he started to work in local cafes and barrooms, but found it hard to compete as a solo violinist. In an unpublished memoir of Europe written later by Sissle, he described how Europe struggled in his early New York days as he tried to establishment himself as a musician:

In those days the Negroes who worked for the wealthy white people were mostly singers and dancers, and the instruments they played were mandolins and guitars. It was this fact that kept [Jim] out of work…It was weeks before he woke up to the fact that it was the instrument he played [the violin] that was keeping him from the “Big Money” he had dreamed of…He was at the point when he must either give up the fiddle or face starvation, so … [he lay] down his favorite instrument and [took] up the mandolin. … Having also been accomplished in piano playing, between the two, he easily got work, and with his organizing ability, it was no longer before he had organized a quartette of players and singers. Before many months had rolled around, we find him…the official musician in the famous Wanamaker Family, which, as Jim often declared was the beginning of his becoming the society favorite of Music producers in the drawing-rooms of New York’s Four Hundred.

Europe’s quartet often performed in the bar at the Marshall Hotel on 53rd Street, then the major spot for black musicians seeking work to be heard by members of society. As Sissle recalled:

It was a famous Black and Tan resort that the Elite of New York usually patronized on slumming expeditions. … there were very seldom any colored patrons there except musicians. Mainly because the prices charged for wine and food were prohibitive for most colored people. It was, however, a place frequented by musicians and entertainers…It was well worth while to come in and give their services because Marshall (who was a Negro) would feed them and the money given them by the wealthy patrons [as tips] was a good amount.

John Love, working as secretary to the mighty Wanamaker family, first heard Europe’s group there performing at the Marshall in 1903, and soon hired him to play for the family’s many social affairs, from weddings to farewell parties before the family embarked on its annual jaunts to Europe. Love noted that “Mr. Rodman Wanamaker was a man of marked tolerance,” a veiled allusion to his willingness to hire black musicians, “but he cannot tolerate mediocrity,” showing that his regular employment of Europe’s band was a reflection of “the excellence of [Europe’s] work.” Europe probably met the major theatrical stars of the day at the Marshall, and was soon working as a bandleader for Williams and Walker and Cole and Johnson. He served as musical director for Cole and Johnson’s successful productions of The Shoo-Fly Regiment (1906) and its followup The Red Moon (1908). In 1908, Ernest Hogan, one of the most popular comedians of his day suffered a nervous breakdown. Europe arranged for a benefit performance to help the ailing performer. The event was so successful the musicians joined together and created a fraternal club, The Frogs, to benefit African-American performers. Europe became a leading member of the organization, appearing at their annual “frolick” in 1910. He also collaborated with the other leading black songwriters of the day.

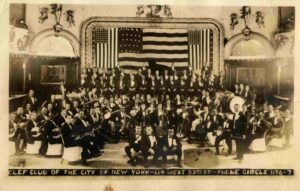

Recognizing the poor conditions faced by blacks seeking employment in New York, Europe established a kind of musician’s union-booking agency-concert promotion-and performing organization called the Clef Club in 1910. The purpose was to offer white patrons a central office where they could book the highest quality black musicians who they would know were vetted for both their talent and reliability. Europe felt it was demeaning to have to rely on chance encounters in noisy clubs like the Marshall Café to find work; plus, he found it embarrassing when asked by his patrons for his contact information only to have to tell them he could be reached only at some lowly barroom. As Sissle recalled, “It was galling for him…to have to give the address of some café or saloon, because there were many people of that set that would not like to be calling up those kind of places…” In order to raise money for a permanent home office for the club, Europe determined the best thing to do was to put on a concert that would showcase its members talents: “He felt sure that from his experience with the [white society] people he had been entertaining,” Sissle said

that a big male chorus and stringed orchestra, with instrumentations such as his fellow musicians had been using, on a small scale ought to prove a big drawing-power for the elite. That is providing the concert was given in a place that those people were used to attending. … Jim [en]visioned a crowd and an income of finance that would enable the Club to get its own Club room, and Headquarters, thus putting their entertaining on a more dignified plane.

Europe bought a house at 136 West 53rd Street to serve as the club’s headquarters, which was incorporated on June 21, 1910. The club soon had 200 members (women were not allowed to join or come into the clubhouse). James Weldon Johnson described the Club:

[James Reese Europe] gathered all the coloured professional instrumental musicians into a chartered organization and systematized the whole business of “entertaining.” The organization purchased a house … and fitted it up as a club and also as booking-offices. Bands from three to thirty men could be furnished any time, day or night. The Clef Club for quite a while held a monopoly of the business of “entertaining” private parties and furnishing music for the dance craze, which was just then beginning to seep the country. One year the amount of business done amounted to $120,000.

In fact, the Clef Club was able to organize several grand concerts, with an orchestra numbering as many as 75-200 pieces, primarily made up of banjos, mandolins, and guitars, the instruments most in use by black performers of the day. These stringed instruments were portable and able to take the place of a piano when some white households wouldn’t let the musicians use their pianos. Europe recalled his frustration trying to get the band together for rehearsal; without offering any pay, he couldn’t be sure that the same musicians would show up each time, and he often had to show the players how to finger the notes of each passage as many did not read music. Europe described how he solved this problem, “I always put a man who can read notes in the middle where the others can pick him up.” In 1910, an ensemble of 100 pieces appeared at the uptown Manhattan Casino located at 155th Street and Eighth Avenue, in a concert advertised as a “musical mélange and dance fest.”